Integrating Trauma and Mental Health Services for Adolescents into Outpatient Care in Western Kenya

By: Brittany M. McCoy, MD1,2,3,4 & Eunice Temet, MBChB, MMED4,5

1Department of Global Health and Health System Design, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, 2 Arnhold Institute for Global Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, 3Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 4Academic Model Providing Access To Healthcare (AMPATH) Kenya, Eldoret, Kenya and 5Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, Eldoret, Kenya

Introduction

In Kenya, children and adolescents under the age of 19 years comprise nearly half of the total population (1). Against this demographic backdrop, ensuring that young people can readily access quality mental healthcare is an urgent national priority. A recent national survey found that 12.2% of Kenyan adolescents (10-17 years) met criteria for a psychiatric disorder (2). However, few had accessed any form of support for their mental health concerns, and families noted a lack of available services as one of multiple barriers to adolescents receiving the mental healthcare they need (2).

Furthermore, studies with Kenyan adolescents have found rates of exposure to potentially traumatic events as high as 94.8% in school-based samples, with 34.5% of those exposed meeting criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD (3, 4). Exposure to traumatic events in childhood has been associated with multiple negative physical and mental health outcomes (5). Given the morbidity associated with childhood trauma and availability of highly effective, evidence-based treatments for childhood traumatic stress symptoms, experts advise screening for trauma and traumatic stress symptoms during pediatric primary care visits to facilitate early identification and intervention (5, 6). Such screening is not yet standard practice in many settings, though, including in Kenya, where models for routine pediatric trauma screening and interventions in outpatient care are understudied (5).

The Angaza Project

With pilot grant funding from the Arnhold Institute for Global Health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, our team is undertaking work to culturally and contextually adapt a model of screening for and responding to trauma and traumatic stress symptoms among adolescents in western Kenya. “Angaza” is a Swahili word meaning “to give light” and is often used to represent hope or opportunity. Through culturally grounded trauma screening and early intervention, the Angaza Project seeks to “give light” by fostering hope and strengthening the resilience of Kenyan adolescents affected by trauma.

Using implementation science methods, including interviews and focus group discussions with key partners, our team is working to collaboratively adapt the Pediatric Traumatic Stress Screening Tool and Care Process Model for Pediatric Traumatic Stress to serve the needs of adolescents and young adults (ages 10-24 years) receiving care at two outpatient clinics based at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) in Eldoret, Kenya (5). Together, these clinics provide care to over 1,100 young people from Eldoret and its surrounding communities. MTRH and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, USA are institutional partners through the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) Kenya consortium (www.ampathkenya.org). The Care Process Model for Pediatric Traumatic Stress is an evidence-based model that guides clinicians on how to appropriately respond to positive screens on the Pediatric Traumatic Stress Screening Tool, including with brief interventions (5). Importantly, this model is intended to be delivered by non-mental health specialists, increasing its utility in settings where access to mental health specialists is limited.

The Angaza Project expands our previous efforts to incorporate culturally adapted tools for routine depression, anxiety, and substance use screening into adolescent clinical care at our partner clinics. As emerging evidence suggests that screening for depression alone misses many adolescents with significant traumatic stress symptoms, the addition of trauma screening will help clinicians to both better identify adolescents with traumatic stress symptoms and more accurately characterize their mental symptoms (7). By doing so, we can help ensure adolescents receive the most appropriate mental health interventions for their concerns earlier.

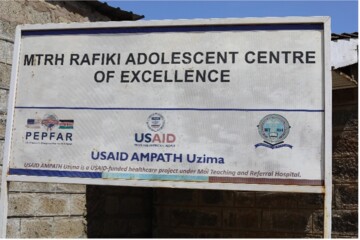

Figure 1 - 3: The MTRH Rafiki Centre for Excellence in Adolescent Health in Eldoret, Kenya serves as one site of the Angaza Project. This outpatient clinic provides youth-friendly healthcare services, including mental health services, to over 870 youth between the ages of 15 and 24 years in western Kenya.

Conclusion

Upon completion of this work, the Angaza Project will have generated a culturally and contextually adapted model for identifying and supporting adolescents who have experienced trauma in western Kenya. Our next step will be to pilot the adapted model in our partner clinics to evaluate its feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness for Kenyan adolescents, their families, and clinical staff and programs. By strengthening the groundwork for a scalable, trauma-informed approach to adolescent care, this project seeks to contribute to improved identification of traumatic stress, more timely support for affected adolescents, and long-term gains in mental health outcomes across western Kenya.

Acknowledgements

The Angaza Project is funded with support from the Arnhold Institute for Global Health at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in partnership with Moi University and Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Mount Sinai or Moi University/Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital.

Figure 4 & 5. Eunice Temet, MBChB, MMED (top) and Brittany McCoy, MD (bottom) serve as co-Principal Investigators for the Angaza Project

Reference

1. UN. World Population Prospects 2022, Online Edition 2022 [Available from: https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/.]

2. Wado YD, Wekesah F, Odunga S, Nyakangi V, Njeri A, Kabiru C. Kenya–National Adolescent Mental Health Survey (K-NAMHS). APHRC; 2022.

3. Karsberg SH, Elklit A. Victimization and PTSD in A Rural Kenyan Youth Sample. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2012;8:91-101.

4. Mbwayo AW, Mathai M, Harder VS, Nicodimos S, Vander Stoep A. Trauma among Kenyan School Children in Urban and Rural Settings: PTSD Prevalence and Correlates. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2020;13(1):63-73.

5. Keeshin B, Byrne K, Thorn B, Shepard L. Screening for Trauma in Pediatric Primary Care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(11):60.

6. Rolon-Arroyo B, Oosterhoff B, Layne CM, Steinberg AM, Pynoos RS, Kaplow JB. The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5 Brief Form: A Screening Tool for Trauma-Exposed Youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(3):434-43.

7. Campbell KA, Byrne KA, Thorn BL, Abdulahad LS, Davis RN, Giles LL, et al. Screening for symptoms of childhood traumatic stress in the primary care pediatric clinic. BMC Pediatr. 2024;24(1):217.

This article represents the view of its author(s) and does not necessarily represent the view of the IACAPAP's bureau or executive committee.